Orient Expression, Telegraph Magazine

For so long persecuted, poor and hidden from the West, Chinese artists are finally enjoying their own cultural revolution. Bettina von Hase visits those at the heart of this renaissance. Photographs by Polly Braden.

Not long ago in the city of Berne, I visited an exhibition of contemporary Chinese art owned by the Swiss collector Uli Sigg. One of the works was a striking black and white painting by the Chinese artist Shi Xinning, in which Chairman Mao and four acolytes stare intently at a urinal. Not any old urinal, but Marcel Duchamp's ready-made icon which launched modern art as we know it. The painting, based on a real photograph of Mao visiting an industrial fair, plays with truth and fiction. Mao never did see Duchamp's work. Shi replaced the real object of their attention with the urinal. But the painting is prophetic on many levels. The artist wills Mao to look at the beginning of Western art, and us to look at a work whose existence and subject matter announces the arrival of the Chinese on the contemporary art scene.

The exhibition made me want to go to China, to see for myself the work being made in this major transition in the country's cultural, political and economic history. Shortly afterwards, I travelled with a group of collectors touring artists' studios and galleries in Beijing and Shanghai, culminating in a visit to the Guangzhou Triennial, the most important contemporary art show in China.

On arrival in Beijing, one of the first artists I visited was Shi, in his modest studio in a former munitions complex, called Factory 798. 'I try to discuss the conflict between two different value systems and put them together in a harmonious framework,' says Shi, a fawn-like 37-year-old with a ponytail. 'It's not what I want to see, it's how I do see the world.' Other works were propped up on the studio walls, using the same technique as the Berne picture, starting with the conceptual idea of creating a doctored photograph which is then painstakingly copied on canvas. There was a half-finished Mao with Marilyn Monroe and Joe DiMaggio, Mao with the Beatles Mao at a mythical press conference All had already been sold to Western collectors and museums, for prices upwards of $20,000, double the previous year's figures. Shi works slowly, but he can't paint fast enough to cope with the demand of dealers.

Cang Xin and part of Communication series, photograph, 1999.

'Some people may feel it's amusing subject matter when they see these pictures, but when I create them I feel heavy, I feel the weight of it,' Shi says. What at first glance seems to a Western viewer like a fun take on Warholesque pop is also a deep investigation into the memory of Mao, still present 30 years after his death in 1976. Mao's influence was also there in the minds of the 30 or so other artists we visited, most of them in Beijing, where about 2,000 artists make a living without any state assistance. The majority we talked to were in their late thirties to mid-forties now established, even famous in their own country after years of persecution, poverty and hard graft. Some have luxurious, gigantic studios just outside Beijing where the rates are cheaper; others live and work in artists' villages, one studio next to the other, like a cottage industry I noticed that most of them have a painting, a china figurine or bust of Mao on display.

Other than Shi, I met the painters Zeng Fanzhi, Fang Lijun. Yang Shao Bin, Yang Qian and Zhang Xiaogang; the sculptor Zhan Wang, who recently had a piece in the Hayward Gallery; the photographers Miao Xiaochun, Wang Qingsong and Cang Xin, all exhibited in the recent Victoria & Albert museum's photography and video show. I met as well the dancer Wen Hui, the female co-director of Living Dance Studio, who creates works in collaboration with contemporary artists such as Song Dong, a performance artist who also works in video and photography. All were at school during the Cultural Revolution, when China closed its doors to the outside world. 'l was born in Mao's time, all my childhood and education was deeply affected by his thoughts,' Shi says, but he could be speaking for all of them. ‘The first sentence I learnt at school was "Long live Chairman Mao". and then I learnt the alphabet. After he died, it continued to affect us. Even though I am living in a modern society now, he is still deeply in my blood. It’s completely different for the younger generation here, who have not lived through it.'

Shi Xinning in his studio

Thirty years on, 'Faster, higher, stronger' - the motto of the Olympic Games, which comes to Beijing in 2008 - applies to China's development as a whole. The country is on the verge of becoming a global superpower — a country that has 23 per cent of the worldk population. about twice the combined number of the United States and the European Union. Small wonder that everyone is toing 10 crack this nut. ‘When you are in a high-speed train you can hardly feel the pace,’ Shi says, but it is hard to believe him. The contemporary art world has woken up to the fact that China is hot. Part of the excitement lies in the fact that Chinese artists were hidden from the West for so long. But since the start of Deng Xiaoping’s liberalisation in 1992 they have emerged as a force to be reckoned with, dazzling collectors and energising the already overheated market.

Some of that creative energy will be on view at this month’s China in London festival. which begins in time for Chinese New Year on January 29. Beijing and London are now fellow Olympic cities and seem to having a flirtation encouraged by Mayor Ken Livingstone, perhaps hoping to attract Chinese investment into the city. Following President Hu Jintao’s visit to London last November and the opening of the exquisite China: The Three Emperors exhibition at the Royal Academy, it is now the turn of contemporary Chinese art, with two installations at Selfridges by Wang Qingsong, currently on show, and Song Dong, from February 15, and a group show, China Coup (at the Hospital gallery in Covent Garden, January 31 to March 24). This show is curated by The Red Mansion Foundation, a non-profit-making organisation supporting cultural exchange programmes between China and the UK through contemporary art. My trip was under the auspices of this Foundation, founded by Nicolette Kwok and her Chinese venture capitalist husband, Frederick, in 1999.

Song, whose work focuses on the impermanence of things, will build a city made entirely out of biscuits and sweets, called Eating the City. Members of the public will be invited to eat the finished sculpture — an integral part of this work. The piece mirrors the incredible transformation of the country’s building boom, where whole streets disappear overnight and skyscrapers rise in a matter of weeks. Wang's installation, Follow Me, in the entire Oxford Street window run, is about the global fascination with shopping.

Beijing’s own pavements are throbbing with energy. There are building works around every corner. I had arranged to meet Wang and his wife Zhang Fang at a restaurant called Silk in the super-modern mixed-use Jian Wai SOHO property development. A former member of Beijing's influential East Village group of performing artists and photographers formed in 1993, Wang creates large-scale tableaux vivants photographed in Beijing's biggest film studios His photographs are marked by a witty take on Chinese society now, particularly its obsession with logos and brands.

It is a long way from the late 1980s and early 1990s, when performance art was very important in China, because it was more elusive: often one- night happenings, they were gone before the authorities had time to get to them. Many performed naked, a revolutionary act underlining the concept of truth in a society where everything was hidden. Out of performance art grew artistic photography, as photographers recorded the happenings; the East Village group on the outskirts of Beijing became the centre of experimental art at that time. Cang Xin, 38, who, like Shi, has his studio at Factory 798, is one of those photographers.

Cang sports a Manchurian haircut, and his work investigates his ethnic identity and the role he plays in society. This may sound like a well-trodden cliché, but for Chinese artists investigation of the individual is of particular significance. China's spiritual and historical legacy — Taoism, Confucianism, Buddhism and Maoism — did not celebrate the individual but the group. ‘We have a different historical background,’ says Victoria Lu, the creative director of Shanghai's Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA). ‘In the European tradition you have religious roots. In China you don't have that. We believe in the sky, in heaven. The heavens rule. In our language, we have no past tense, no future tense. Sense of time is very vague. The universe is the important factor, not the individual. Look at feng shui — the Chinese have learnt over thousands of years to live with whatever is around them. There is a strong ability to adapt.’

Cang’s work is the visual embodiment of words. In his photography series, The Unification of Heaven and Man, his naked body appears as a piece of sculpture made by nature; in his ongoing Communication series, he ritualistically touches objects considered important to the Chinese with his tongue, such as wood, a mahjong (the national game) piece and money. The subject matter of all the work I saw in China is the relationship between tradition and modernity, China and the West, the individual in a rapidly changing urban environment, and the consequent anxiety and loss of innocence.

China’s relationship with the West is being tested as it prepares to play host to the Olympics. It was awarded the Games in 1997, eight years after the Tiananmen Square Massacre, which swung world opinion against the government. Even now, the West is ambivalent about China with its human-rights violations and economic might. 'The Games are an affirmation of China's aspiration to be a world player.' Wang says. It has not escaped the authorities' attention that contemporary art is a brilliant tool with which to attract the goodwill of discerning foreigners visiting China, and an ever- growing Chinese bourgeoisie. who can afford to build their own art collections and private museums to display their wealth. 'The effort made by the government publicising the Olympics, it was like the Cultural Revolution,' Wang says. 'The government is now saying, "You should help us look good to the outside world." But art no longer has to resemble propaganda to be useful to the government’s public relations.

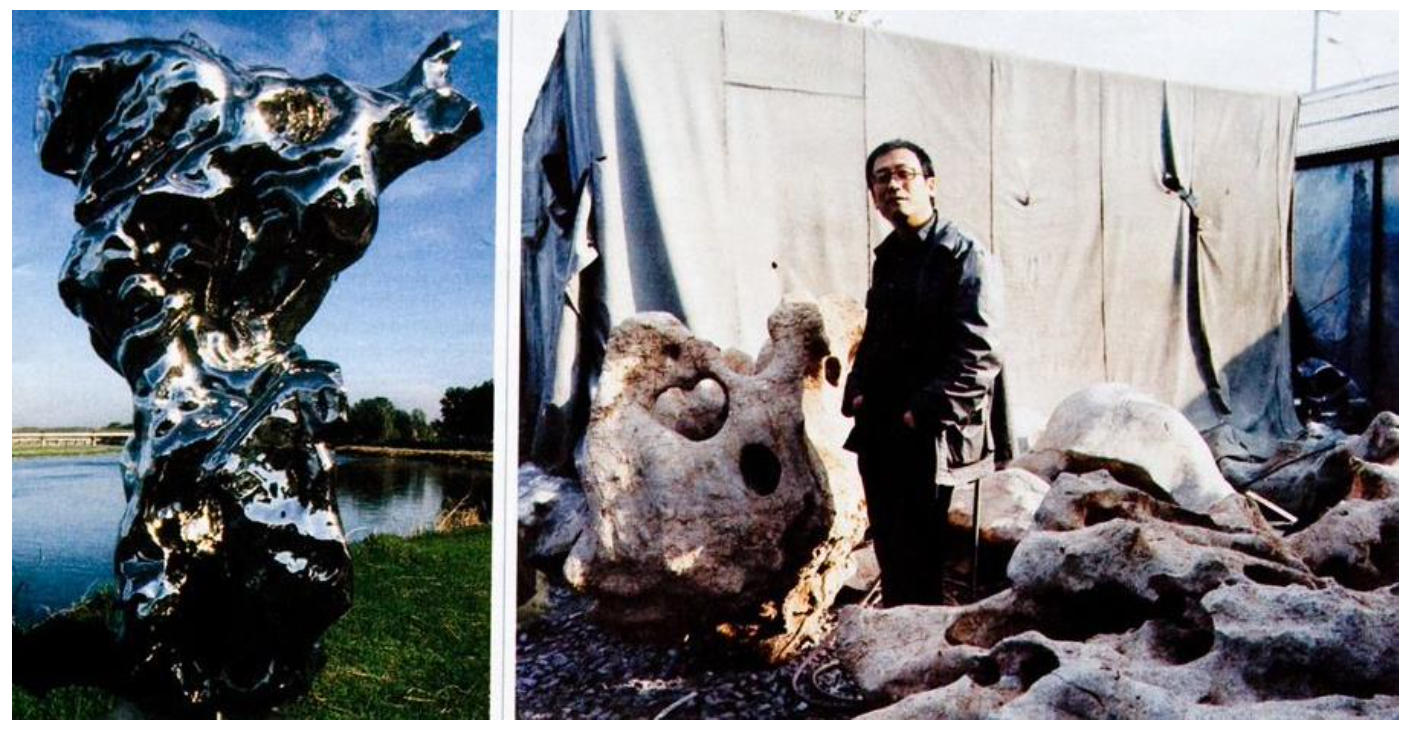

The Chinese government wants to build 1,000 museums by 2015, in Shanghai alone 30 by 2010, when the city hosts the World Expo. It’s a mind- boggling number considering that people are only just beginning to think about what to display inside — the ‘software’, as Hans-Ulrich Obrist who, together with Hou Hanru, curated the Guangzhou Triennial, calls it. One ‘software provider’ inspired by the new building boom is the sculptor Zhan Wang, whose stainless-steel-covered scholars' rocks are highly sought after by both Chinese and Western collectors. Zhan was inspired to make the sculptures by the many new buildings that, according to him, were crying out for contemporary art to match them. ‘Only contemporary art can truly represent China to the West. as it is the only thing that develops naturally out Of China,’ he says.

The most exciting aspect of China's emerging art is that all the artists are reconnecting to their own roots, traditions and techniques, having spent time looking at and being influenced by Western art. Characteristic of this experience are the painters we visited. ‘I got a culture shock when I arrived in America,’ says Yang Qian, who paints dreamy nudes in steamy bathrooms (‘In the bathroom mirror, things are not so clear’) and who left China to study in New York in the mid-1980s. ‘Can you imagine the feeling of seeing the originals of Van Gogh, Rauschenberg, Lichtenstein for the first time?’ he asked me. ‘We all studied Western painting at the academies in China, but as late as 1984 the art form stopped at German Expressionism in the 1950s — if you painted in a style more recent than that, you would have trouble politically.’

Now, nothing seems to be off limits. The resulting creative freedom has led to a visual sensation and acts as an incentive to look closer to home. In Shanghai, Zhou Tiehai made the Western. influenced placebo series of airbrushed paintings where a head replaces the heads of portraits copied from classical masterpieces of da Vinci, Goya and Ingres; his new work is a contemporary take on classical Chinese brushstroke painting.

Wang suspended in a spider's web of luxury goods in a recent installation at the Beijing film studios

Wang Qinsong, whose work investigates the global obsession with logos and brands

‘It's not an East-West game,’ says Meg Maggio, the Beijing-based director of Pekin Fine Art Consultancy. ‘Westerners are going to become less important to the market. They don't get the pace. You can't underestimate the Chinese diaspora, who have been buying for the last 15 years, and the mainland buyers, too. are really excited by contemporary art and auction prices in their own country.’ The stakes are raised, now that Chinese artists have arrived with such fanfare: ‘The works increasingly are being recognised simply as excellent contemporary art and no longer pigeonholed as Chinese,’ Amelie von Wedel of Red Mansion says.

One of the artists both collectors and dealers are excited by is Zhang Xiao-gang, some of whose Bloodline series of pictures sell for more than $100,000. We visited his studio in the artistic community of Suojiacun, north-eastern Beijing (which was — shockingly — pulled down and demolished by a developer the day we left China, something that apparently happens on a regular basis). ‘Everything is moving so fast that the Chinese are hovering between memory loss and remembering,’ Zhang says. ‘I am trying to show the spirit of human beings in this state. They don't want to abandon history.’

Miao's Opera, 2003

His colleagues Zeng Fanzhi and Fang Lijun would agree. Now classical masters whose works also command $100,000 plus, they came out of a group of painters marked by the Tiananmen Square crackdown. Zeng's famous Mask series done in the late 1990s shows groups of people wearing close-fitting white masks as a second skin, looking tense and ill at ease in their seeming cheerfulness. Fang, known for pictures of identical bald heads of grinning or screaming Chinese, is known as the Chinese Damien Hirst. He showed us bronze sculptures. of faces with feet attached, in various expressions of ludicrous desperation.

The same could not be said for the artists themselves, who all looked uncannily alike, with their balding heads, expensive black leather jackets, huge modern studios and attractive female companions who usually translate for them, and seemed, at least when I met them, to be firmly in control, I asked Wen Hui, the one female artist we met in Beijing, about this. Wen, 45, told me that there are now more women artists than 10 years ago, but that ‘women are still behind the man. Women are contemporary, but inside they are still traditional.’

Walking around the 2nd Guangzhou Triennial, I was struck by the makeshift atmosphere, accentuated by the display, with wooden planks and scaffolding giving the impression of a building site. The inherent tension between this provisional set-up and the undoubted quality of the art on show was actually a perfect description of what’s going on in the country itself. Obrist — who has just become co-director of the Serpentine Gallery in London - and his colleague Hou wanted to demonstrate the country’s diversity by concentrating not on a city but on a whole region: ‘The boom in China is only just beginning,’ Obrist says. They gave artists their own spaces to make installations or curate their own shows — in a car-park, on the site of what was once a women’s prison. ‘We wanted to show that it wasn't curated only by us. In a complex situation, why should two curators know everything?’

Complex it may be but one thing is clear: talking to his artist friends, Obrist says, ‘New York artists want to live in Paris, London artists want to live in Berlin, Paris artists want to live in London. But Chinese artists only want to live in China.’ None of them wants to leave, because they know that they are in the right place at the right time.

Miao Xiaochun, whose work combines large-format photography with digital technology, in front of his Mirage (2004), a panoramic view of Wuxi, the town where the artist grew up.