My future is now - not next year or the year after

One year has passed since I was diagnosed with breast cancer. Some mornings, in the transitional state from sleeping to waking, I still cannot believe it happened to me. Up until then my life had been blessed and stressed.

I had grown up in Britain as my father was the German ambassador in the Seventies. I loved my English life. London was a very different place to the global boomtown it is today; I was fascinated by its architecture and sheer eccentricity. I read history at Oxford, was a foreign correspondent for Reuters, a television producer for CBS News and then a management consultant working with prominent media and arts clients.

In the late Nineties, I set up my own arts consultancy, Nine AM, and worked all hours of the day and night to make it a success. The art world is international and 24/ 7 and I found my business and social life merging seamlessly into each other. It was a frenzied time and my life was so full that the lump I felt in my left breast at the tail-end of a summer holiday did not alarm me I simply didn’t stop to think it would be malignant.

Cancer suddenly stopped me in my tracks. My health had always been very good, but now I realise I had neglected it. I didn’t acknowledge that my stress levels were often much too high, and my diet never included the requisite amount of greens and fruit. Neither did I have regular breaks when I truly rested. So it took me two months to make an appointment with my GP, and then another three for the hospital to give me a confirmed date, valuable time which in retrospect I wished had not been wasted.

I remember the diagnosis in March 2006 at St Marys Paddington like it was yesterday the shock of it, the arrival of fear as my constant companion.

I moved to the Royal Marsden Hospital, where I had a mastectomy of my left breast last April, followed by five months of chemotherapy, the most corrosive invasion of chemicals to the body. One of the many invidious aspects of cancer is that often the treatment makes one feel ill, not the disease. I was nauseous and my energy was zapped. One month after starting the chemo-cycle, I saw a reflection of myself in a shop window, a hairless creature struggling to take a few steps up to Notting Hill Gate to buy an ice cream to kill the metallic taste in my mouth.

The care I received was good, but the mental and physical challenges are still there for me to deal with. The loss of the two most feminine parts of the female body, hair and breast, is shocking at first. My waist-length dark hair which had been my trademark look since my teens was chopped off to avoid losing long strands in bulk; when 80 per cent fell out within three days, exactly three weeks after my first chemo, my hairdresser Bryan advised me to shave it off completely, and did it there and then.

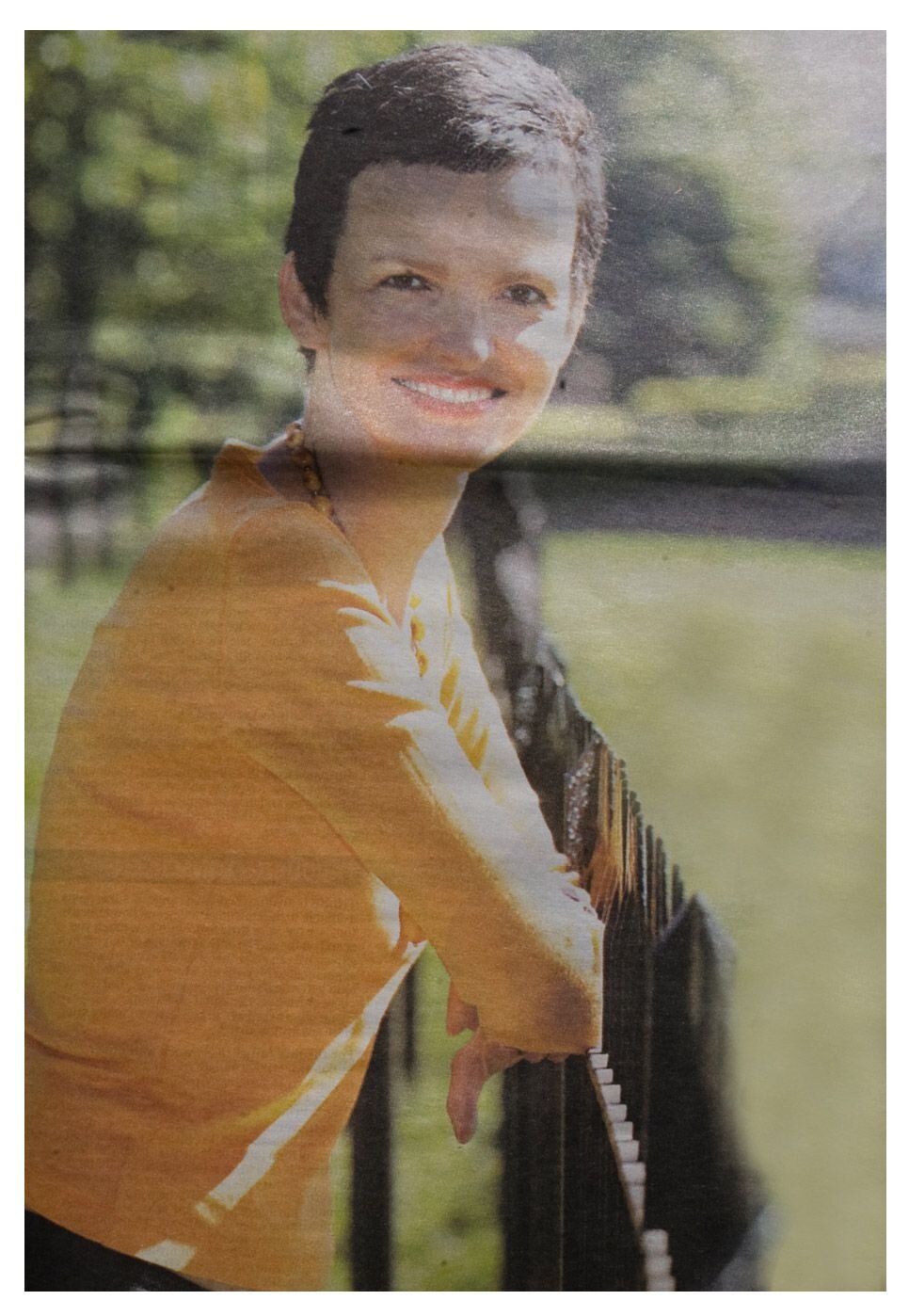

I bought a wig, and now my hair has started to grow back into a short crop, not yet quite like Kylie Minogue, but almost. I always had a secret fantasy about really short hair, but never the bottle to cut it. Now I just enjoy it, particularly because short hair demands a whole new look think Audrey Hepburn. I was helped enormously in all this by my boyfriend, who played a large part in my emotional recovery.

He became my guide through the new landscape. He was excited by my bald head, saying it was futuristic and beautiful. He took away the fear of being mutilated or scarred, telling me he’d still adore me with three breasts, or two or none. You have to face the harsh fact that your body is never the same again, whether you have a reconstruction or not. I had a brilliant one, but I miss the symmetry of old. And because of the reconstruction I have a large scar on my back.

Cancer gives your life a new definition, whether you like it or not. Priorities are realigned. My diagnosis into a parallel universe: waiting in hospitals and doctors’ consulting learning new medical terms and listening to concerned voices who spoke bad news. It was a period of high anxiety which I could not have borne without the constant reassuring presence of my assistant, Amanda, and my youngest sister Geli accompanied me to every single doctor’s appointment and made “breast” files of the rapidly increasing paperwork, the truest sign of love I have ever received.

But as we ground through all the appointments and planning and research, a bleak shock was waiting. I did not know that if breast cancer spreads, it tends to go to the bone first. Last October, just when I thought I was getting back on track after completing chemotherapy, I developed a backache.

Finally, I had the MRI scan I had wanted ever since I was first disgnosed, but which was deemed unnecessary as my lymph node sample had tested negative. The scan showed that the cancer has metastasised to my spine and rib cage. I had moved from eary to advanced breast cancer.

I remember hearing the voice of my principal doctor, Professor Ian Smith, head of oncology at the Royal Marsden, and thinking “How can I live with that?” I asked him how long I had got, but in truth there is no definite answer – everyone’s cancer is individual, and the drugs I am on have only been on the market for three years, too short a time for statistics. Smith said something to me which I did not believe at the time, but later found not only true but helpful: but helpful: The fear of death is a feeling that comes in waves and loses intensity over an ongoing period. The physical symptoms, dry mouth, sweaty hands, tingling scalp, rising panic, fade after a while. You learn to live with it. You have no other choice.

The second diagnosis was a pivotal moment. At an early stage breast cancer may be serious, but after the initial impact there is a real chance you can beat it. It can be curable at a stage when it has not yet spread to other parts of the body. Metastatic breast cancer is unknown territory.

The reminder of your mortality is concrete, and with it all existing assumptions about your life are swept away. The language of my doctors changed. They said they could not "cure" it any more. but could "contain" it — for how long, no one knew. The only good news was their strongly held belief that breast cancer was on the verge of being transformed into a chronic disease, with new drugs and treatments expected to make all the difference and extending life span.

Cancer is a "systemic" disease — once it has spread. there is currently nothing that can eradicate it. On my bad days, I feel like I'm walking around with a time- bomb in my body. which can go off at any time. But I try to lead a normal life. I work as before. and I find it a solace rather than a chore. I do not want to be defined by my illness. and the best way for me to avoid that is to be straight if people ask. then quickly move on to other things. I have adapted to the disease — but I don't let it rule me.

Really, I hadn't thought about it at all before. Maybe it was because I was diagnosed in my forties, when the illness seems to proliferate. Before, it was an illness for others. but now I realised it was all around me. It seems that many more women than one in nine — the official UK statistic develop it, and I find it astonishing that NHS screening starts only at age 50. Talking to my American, German. Italian and French friends, I noticed that they started screening a good 10 years earlier. which means that early detection can be life-saving.

I tell all my younger girlfriends to be vigilant. more vigilant than I was because once have breast cancer. it is agonising to deal with. I decided not to keep it from my friends. not to "disappear". but to integrate it into my life.

My body and mind have learned to surrender to other people's help. not easy for someone who has always been a self-starter. "Cancer is bad for business", an American friend told me half in jest when I was in hospital. but for me it turned out differently The silver lining in my big black cancer cloud was the fact that my family, friends, clients and colleagues came up trumps in more ways than I could ever have imagined. The word is loaded, but the reality is that many people live with cancer for many years. A rush of love and support overwhelmed me, and as a result I am determined to conquer the disease and defy the odds.

Since my second diagnosis I have had a series of five radiotherapy treatments, described as "palliative", which means it alleviates the pain rather than shrinks the tumours. I take Femara daily, an aromatase inhibitor which blocks the oestrogen that feeds my cancer, and receive a monthly transfusion of bisphosphonates to strengthen my bones. I go every month for outpatient treatment at the Royal Marsden.

I research and inform myself, without — I hope — being obsessive. It also means insisting on tests I might want to have, whereas my doctor thinks they may not be crucial — my peace of mind is. I also have a new respect for my body, the battering it has endured. and I take better care of it. I sleep well, I rest frequently, I take regular breaks, and I eat much more healthily. It is also beneficial to have enjoyable and achievable goals. Mine are to nurture my family and friends, develop my work, write a novel, have a place by the English seaside, and learn Spanish.

The future is now, not at some ill-defined fuzzy point next year or the year after. I have a councillor to talk to, who can see the glass as half-full when I see it as half-empty. The most important part of my life is not to lose my sense of optimism. This has been made easier by the fact that recent scans — the first since my treatment started — showed the tumours on my spine had considerably shrunk. After one long year. I feel things may be turning around. Best of all, I have a deeper appreciation of living day to day, and all that offers. It may be uncertain, but at some level, everyone's is. But not everyone knows how valuable it is. I wish it hadn't taken cancer to teach me this lesson, but I’ll make the most of my life – however long I’ve got.